Machine Learning progress is impressive, but we argue that progress is still largely superficial.

What’s wrong with current Machine Translation models?

Machine Learning models are still largely superficial – the models don’t really ‘understand’ the meaning of the sentences they are translating. If we want increasingly ‘intelligent’ machines, it’s important that models begin to incorporate more knowledge of the world. One approach to achieve this is to require models to be good, not only at translation, but additional tasks, such as question answering. A parallel direction is to encourage models to internally focus on the meaning of the sentence. This post summarises our approach to this latter direction, published at NIPS 20181.

Learning meaningful representations of data

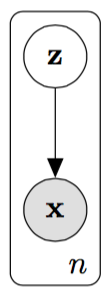

Latent variable models in natural language processing typically posit the following generative process for sentences:

- A ‘hidden’ or ‘latent’ representation is randomly generated according to a prior distribution.

- The sentence itself is then generated conditioned on this latent representation.

Given a latent variable model and a sentence, the posterior distribution of the latent representation (i.e. the values of the representation that are likely to have generated that sentence) can be inferred. This posterior distribution can then be used for downstream tasks, e.g. the inferred representation could be used for answering questions about that sentence. Intuitively, the more information about the meaning of the sentence that the representation contains, the better it should be at performing at downstream tasks. Therefore, we would like to design a model which can use its latent representation to better represent the semantics of the text.

Most latent variable models use one latent representation per sentence in the data set. The problem with this approach is that there are no guarantees that the representations will learn semantically meaningful information about the text. For example, consider the two sentences: “she walked across the road” and “the woman crossed the street” - a basic latent variable model does not know a priori that walking across a road and crossing a street are similar actions. Therefore, the typical model would not be able to guarantee that the latent representations of these two sentences are similar.

Instead, if we were able to encode into the model that two sentences are semantically similar, we may be able to learn representations which better understand the meaning of the text. Unfortunately, large corpora of sentences with similar meanings in a single language are rare. However in the machine translation context, the same sentence expressed in different languages offers the potential to learn a latent variable model which better represents the sentence’s meaning. For example, a model which knows that the English sentence “the woman crossed the street” and the French sentence “la femme a traversé la rue” have the same meaning should be able to learn a representation with better semantic understanding.

Generative Neural Machine Translation (GNMT)

With Generative Neural Machine Translation (GNMT)1, we use a single shared latent representation to model the same sentence in multiple languages. The latent variable is a language agnostic representation of the sentence; by giving it the responsiblity for modelling the same sentence in multiple languages, it is encouraged to learn the semantic meaning.

For each data point in a data set, typical latent variable architectures model the joint distribution of the latent representation and the observed sentence as:

where are trainable parameters of the model.

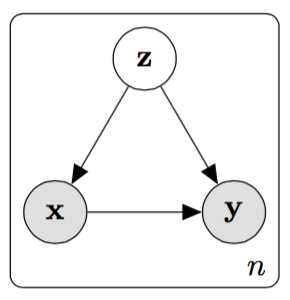

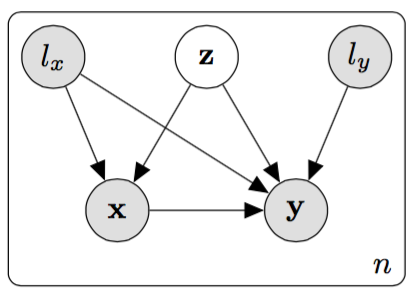

Instead of modelling a single sentence per latent representation, GNMT uses a shared latent representation to model the same sentence both in the source and target languages. GNMT models the joint distribution of the latent representation, source sentence and target sentence as:

This set up means that models the commonality between the source and target sentences, which is the semantic meaning.

For full details on the neural networks used to model the distributions of the source and target , see 1.

One may argue that it would be better if the target sentence were dependent only on the latent representation and not directly on the source sentence, giving the model – forcing the latent representation to be fully responsible for generating both the source and target sentence. However, we found that the generated translations weren’t sufficiently syntactically coherent.

Training the model

We use the Stochastic Gradient Variational Bayes (SGVB)23 algorithm to train the model described above. SGVB introduces a ‘recognition’ model which acts as an approximation to the true but intractable posterior , thus forming the following lower bound on the log likelihood of the observed data:

The model parameters and recognition parameters are then jointly learned by performing gradient ascent on this lower bound.

Generating translations - the ‘banana trick’

Suppose the model has been trained, and then we are given a sentence in the source language () and asked to find a translation of that sentence. In this scenario, we want to find the most likely target sentence conditioned on the given source sentence. The natural objective is therefore:

However this integral is intractable, and so we cannot perform this maximisation exactly. Instead, we perform approximate maximisation by iteratively refining a ‘guess’ for the target sentence. We first make a random guess for the target sentence, and then iterate between the following two steps:

- Draw samples of the latent representation from the approximate posterior, using the source sentence and the latest guess for the target sentence.

- Update the guess for the target sentence based on the latent representation samples from step 1. This update is done by choosing to maximise .

Intuitively, this procedure computes the values of the latent representation that are likely to have generated both the source sentence and the latest guess for the target sentence. It then improves the guess based on those values of the latent variable. Mathematically, this iteratively increases a lower bound on until convergence and is an application of the Expectation Maximisation algorithm, here playing the role of parameters.

Note: in our group we refer to this as the ‘banana trick’ because we are first aware of its usage in exercise 5.7 in 4, discussing a ficitious protein sequence in bananas.

Below, we show an example of a long sentence translated from English to French by GNMT. The long range coherence of the translation is a good indicator of the model’s ability to capture semantic information about the sentence within the latent representation.

Source: Dans ce décret, il met en lumière les principales réalisations de la République d’Ouzbékistan dans le domaine de la protection et de la promotion des droits de l’homme et approuve le programme d’activités marquant le soixantième anniversaire de la déclaration universelle des droits de l’homme.

Target: The decree highlights major achievements by the Republic of Uzbekistan in the field of protection and promotion of human rights and approves the programme of activities devoted to the sixtieth anniversary of the universal declaration of human rights.

GNMT: In this decree, it highlights the main achievements of the Republic of Uzbekistan on the protection and promotion of human rights and approves the activities of the sixtieth anniversary of the universal declaration of human rights.

Dealing with missing words

Because GNMT’s latent representation captures information about the meaning of the sentence rather than just the syntax, it is able to produce good translations even when there are missing words in the source sentence. The procedure for generating translations is similar to that described above – however in this scenario we also have to refine a guess for the missing words in the source sentence.

We first make random guesses for the missing words in the source sentence and for the target sentence, and then iterate between the following three steps:

- Draw samples of the latent representation from the approximate posterior, using the latest guesses for the source and target sentences.

- Update the guess for the source sentence based on the latent representation samples from step 1. This update is done by choosing to maximise .

- Update the guess for the target sentence based on the latent representation samples from step 1 and on the updated guess for the source sentence from step 2. This update is done by choosing to maximise .

Below is an example of a sentence translated from Spanish to English, where the struck through words in the source sentence are considered missing. Using its latent representation, the model does remarkably well at imputing what the missing words may be and translating them accordingly.

Source: Expresando su satisfacción por la asistencia que han prestado a los territorios no autónomos algunos organismos especializados y otras organizaciones del sistema de las naciones unidas, especialmente el programa de las naciones unidas para el desarrollo.

Target: Welcoming the assistance extended to non-self-governing territories by certain specialized agencies and other organizations of the United Nations system, in particular the United Nations development programme.

GNMT: Expressing its gratitude for the assistance given to non-self-governing territories by some specialized agencies and other organizations of the United Nations system, in particular from the development programmes of the United Nations.

Cross-language parameter sharing

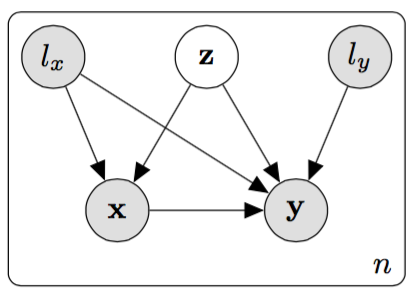

With the architecture described above, if we wanted to translate between, say, English (EN), Spanish (ES) and French (FR), we would have to train 6 separate models for EN → ES, ES → EN, EN → FR, etc. However because all three of these languages share somewhat similar structures, we may not lose much performance by sharing parameters. We therefore add two indicator variables to the model, one for the input language () and another for the output language (). By doing this, we only have to train a single model to translate between three languages, instead of having 6 separate models.

The joint distribution of the latent representation, source sentence and target sentence becomes:

We refer to this version of the model as GNMT-Multi.

Overfitting is a phenomenon whereby a model is too closely fit to a particular set of data points. In machine translation, this often occurs when there aren’t enough paired sentences for the model to learn from. However, the cross language parameter sharing used for GNMT-Multi helps to mitigate this issue. This is because 6 separate models are essentially condensed into a single model, meaning that there aren’t enough parameters to allow the model to memorise the training data.

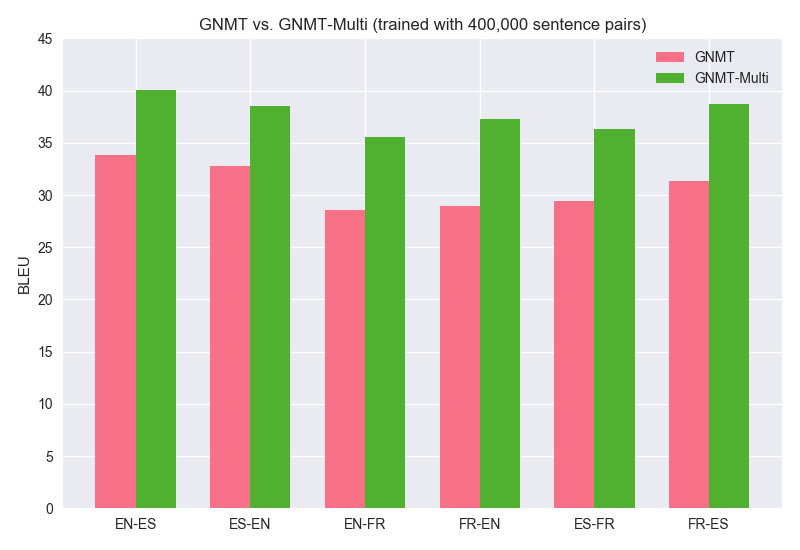

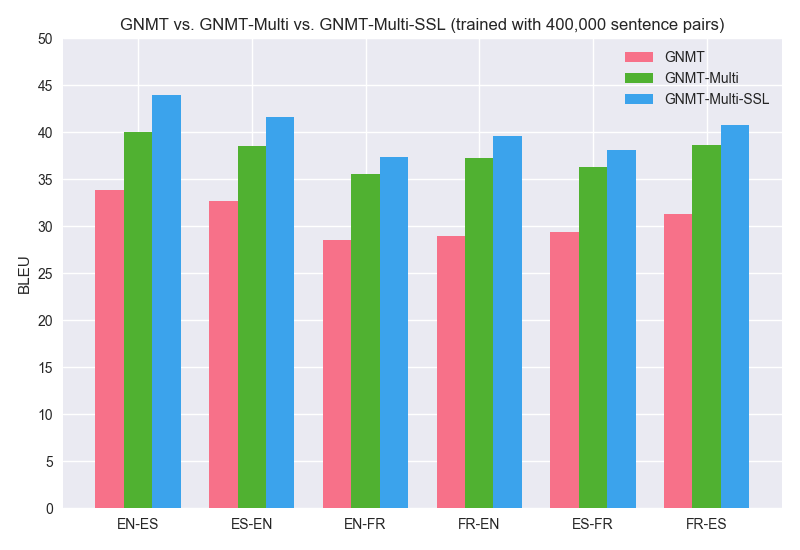

Below, we plot the BLEU scores comparing GNMT-Multi against 6 separate GNMT models, trained with only 400,000 pairs of translated sentences. BLEU is a measure of how well the generated translations match the true target sentences; higher is better. Clearly GNMT-Multi with a limited amount of available training data performs significantly better than each of the 6 separate GNMT models.

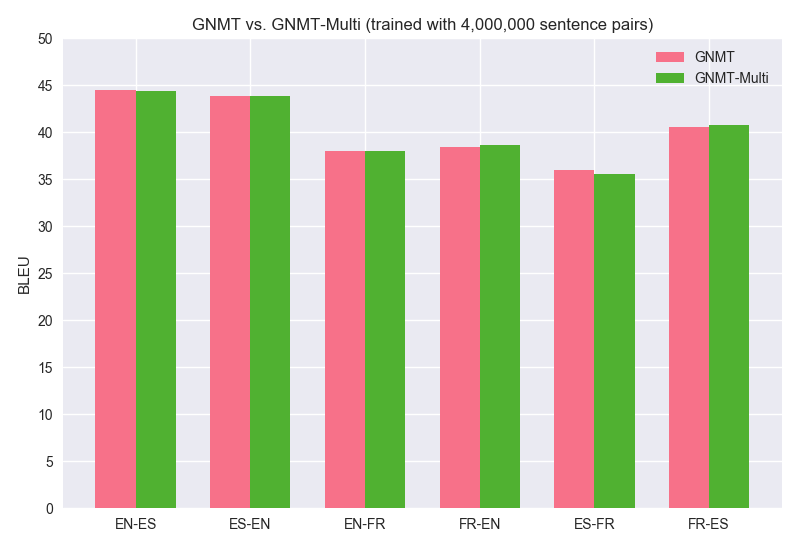

When there is a large amount of training data available, we find that there is very little difference in the performance of GNMT and GNMT-Multi. Below, we plot the BLEU scores for the models trained with 4,000,000 sentence pairs; we find that there is no degradation in performance due to sharing parameters across languages!

Semi-supervised learning

Suppose, as in the previous section, that we only have access to a limited number of paired sentences, but that we now have available lots of untranslated sentences in each language. To learn from untranslated sentences, we can set the input language and output language to the same value, so that the model learns to reconstruct the sentence instead of translating it. Intuitively, this should further help the model to learn the structure and style of each language and thus produce more coherent translations at test time. We refer to this version of the model as GNMT-Multi-SSL.

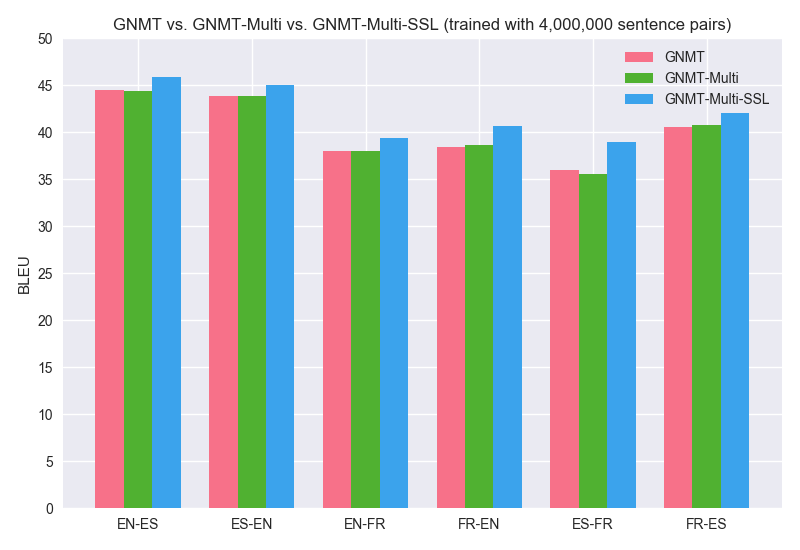

Below we plot the BLEU scores of GNMT-Multi-SSL, GNMT-Multi and the 6 separate GNMT models. They are trained first with 400,000 then with 4,000,000 pairs of translated sentences. In both cases, they are also trained with approximately 20,900,000 untranslated English sentences, 2,700,000 untranslated Spanish sentences and 4,500,000 untranslated French sentences. GNMT-Multi-SSL clearly helps to mitigate overfitting when there are limited paired sentences available. In fact, GNMT-Multi-SSL trained with only 400,000 paired sentences performs about as well as each of the 6 separate GNMT models trained with 4,000,000 sentences! GNMT-Multi-SSL also produces higher BLEU scores even when there is lots of paired data; this verifies our intuition that adding monolingual data helps the model to develop a better understanding of each language individually, and output more coherent sentences accordingly.

Summary

We introduce Generative Neural Machine Translation (GNMT), which is a latent variable model that uses sentences with the same meaning in multiple languages to learn representations which better understand the semantics of the text. It can be used to translate a source sentence by iteratively refining a guess for the target sentence and updating the latent representation accordingly. Because it captures the meaning of the sentence, GNMT is particularly effective at producing translations when there are missing words in the source sentence. We also introduce GNMT-Multi, which is a single unified model (instead of one per language pair) to mitigate overfitting when there is limited paired data available. Finally, we leverage large amounts of untranslated sentences to help the model to further learn the structure and style of each language and produce more coherent translations.

References

-

H. Shah and D. Barber. Generative Neural Machine Translation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

D. Kingma and M. Welling. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2014. ↩

-

D. Rezende, et al. Stochastic Backpropagation and Approximate Inference in Deep Generative Models. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR 32, pages 1278–1286, 2014. ↩

-

D. Barber. Bayesian Reasoning and Machine Learning. Cambridge University Press, 2016. ↩

Learning From Scratch by Thinking Fast and Slow with Deep Learning and Tree Search

Learning From Scratch by Thinking Fast and Slow with Deep Learning and Tree Search